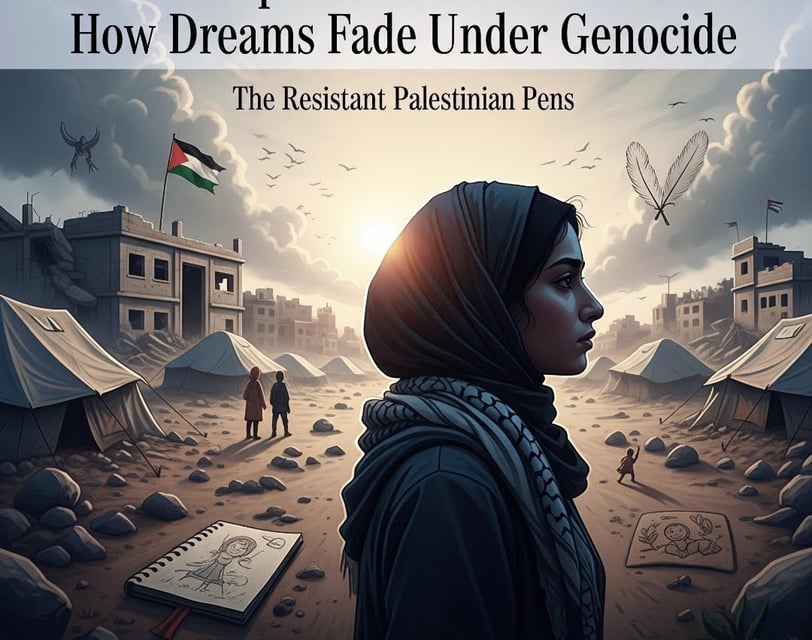

The Displaced Do Not Dream ... How Dreams Fade Under Genocide

In Gaza, displacement has shattered more than homes; it has murdered dreams. This article explores how war, loss, and constant fear have stripped people of their ability to imagine a future, turning the basic human right to dream into an unbearable luxury.

Refaat Ibrahim

7/14/20254 min read

In scattered tents atop the rubble of cities, in doorless schools, or in crowded corners that have lost their names, the displaced in Gaza reside, but they do not live. Their bodies are here, but their souls are trapped in the remnants of memories of homes crushed, schools burned, and streets that once led to life.

They do not dream. When a person is stripped of everything, they are also stripped of the ability to look toward tomorrow. In the tents, the horizon shrinks to two meters of fabric, a bottle of water, and a piece of bread. Who can dream within such confines?

In the harsh conditions of displacement, where there is no stable shelter, no privacy, and no safety, dreaming transforms from an innate right into a distant luxury. Not because they do not wish to dream, but because they simply can no longer.

How can a university student dream of completing their studies while sleeping on the ground, searching for internet in abandoned corners, and spending their day in relief queues? How can a primary school girl dream of becoming a doctor when she has no notebook, no water, and no place to sit without being scorched by heat, drenched by rain, or gripped by fear?

Dreams themselves have become a rare currency, something others in the world talk about and trade in, while we here discover they are no longer available to us. Dreaming has become a luxury, a luxury for those who have lost their homes, families, identities, clothes, privacy, and everything that tied them to a former life.

How does one dream when stripped of everything, with utter cruelty and degradation, and cast into the open, surrounded by pain from every direction?

And what do we say to those whose dreams were grand? Those who toiled, persevered, stayed up late, and made plans for their future? What do we say to the medical student who dreamed of returning to Gaza to open a clinic for the poor, only to find herself standing in a long queue waiting for a bottle of contaminated water?

What do we say to the young man who designed tech projects and sought funding opportunities, now carrying sacks of flour on his back for his family in the camp?

These people do not merely think of what was lost; they live with the constant pain of comparison. Every moment of silence, every glance into the void, carries an unbearable chain of images: “I wanted... It could have been... If only this hadn’t happened...” A heavy silence descends, not because there is nothing to say, but because everything that could be said hurts.

They walk a tightrope between memory and reality. Memories burn like embers: an image of their home, laughter from a balcony, a conversation about the future one evening. Reality besieges them: confinement, cold, anxiety; nothing is stable, nothing is clear, nothing promises anything.

Dreams do not grow in the shadows, nor in the cold, nor under the sound of warplanes. Dreams need safety, a place, time, and an ordinary life. But in Gaza, where the bombing never stops, displacement repeats, and the future seems a dark nebula, dreams wither and die, silently.

What do we say about the youth? Those who once filled the streets with ambition, weaving their futures with creativity and initiative. They designed apps, wrote poetry, painted stunning artworks, and dreamed of opportunities, scholarships, travel, and achievements.

Today, you find them in tattered tents, in queues for water, in empty markets searching for scraps of food, gazing at the bleak sunset in their endless loss and sorrow, without words, without projects, without plans.

And then there are the talented: the musician who lost his instrument, the painter who can no longer find paper, and the writer whose notebooks were burned under the rubble. The tools of dreaming have been broken, their details scattered, their voices slaughtered. You see a young man sitting among the crowd, but he is not there.

Sunk in his silence, he wonders, “Am I still who I was? Or have I become someone else, someone who does not resemble the person I saw in my dreams?” You see a mother staring at her child’s face, wondering if he will live long enough to dream at all. And you see a child drawing something incomprehensible in the sand... perhaps a house, perhaps a window, or perhaps an image from an unfinished imagination.

Repeated displacement has destroyed the human spirit before it destroyed the place. People no longer think about what they will become in a year but what they will eat in an hour. Time itself has been stolen. This is genocide in its deepest form: it does not only kill the body but also kills what that body could become tomorrow, its imagined image, its possibilities, its potentials.

In Gaza, dreaming has become a psychological burden. To dream, one must believe that life is possible, that tomorrow is coming, and that there is a chance. But when a child sees death closer than a piece of candy and warplanes closer than the light of electricity, they do not dream; they only tremble.

And yet, despite all this, the displaced cling to what remains. They sometimes speak of tomorrow, even if tomorrow is merely a wish that their place will not be bombed at night. Some smile despite their loss, not because they are okay, but because they are trying to convince themselves that they are still human, that life, however small, must go on.

But the undeniable truth is this: in Gaza, dreams are not just dead, they are murdered. Killed by the siege, the displacement, the international silence, the complicity, and the betrayal.

The displaced do not ask for miracles, nor do they speak of luxury. All they want is for dreams to return to their sleep, for dreams to be possible, for there to be a tomorrow that is built, not destroyed, and a future that is drawn, not erased.

Awareness

Documenting reality, amplifying Palestinian voices, raising awareness.

Contact Us:

resistant.p.pens@gmail.com

Follow our social media